17.1 Introduction

In this course, we have looked at three different but related logics. In Propositional Logic, we focussed on logical operators. In Relational Logic, we extended our language to include variables and quantifiers. In Term Logic, we added compound terms.

Each of these logics is effectively an extension of its predecessor. The languages are increasingly expressive. The semantics of each builds upon the semantics of its predecessors. And the proof methods of each extend the proof methods accordingly. In fact, we can think of all three of these logics as parts of a single overarching logic that includes the details of all of them, viz. Herbrand Logic.

We begin this final chapter with a review the main concepts of Herbrand Logic. There is nothing new here, just a reminder of the essential details, compressed here into a few pages - to emphasize the important ideas in the course and to make clear how they are related to each other. With that behind us, we look at some extensions to Herbrand Logic, indicating areas for further study and research.

17.2 Review

The language of Herbrand Logic allows us to express simple facts (as ground atoms) as well as more complex forms of information (using logical operators, variables, and quantifiers), as in the following sentence.

∀x.(p(x) ⇒ ¬q(x,x))

The Herbrand base for a logical language is the set of all ground atoms that can be formed using the vocabulary of our language. For example, the following is the Herbrand base for a language involving two object constants a and b, one unary relation constant p, and one binary relation constant q. In this case, the Herbrand base is finite. In the presence of function constants, the Herbrand base is infinite.

{p(a), p(b), q(a,a), q(a,b), q(b,a), q(b,b)}

A Herbrand model is an arbitrary subset of the Herbrand base. The sentences included in the model are assumed to be true, and those that are excluded are assumed to be false.

{p(a), q(a,b), q(b,a)}

A Herbrand model can be formalized equivalently as a truth assignment. Formally, a truth assignment for a propositional vocabulary is a function assigning a truth value to each element of the Herbrand base. In what follows, we use the digit 1 as a synonym for true and 0 as a synonym for false; and we refer to the value of a constant or expression under a truth assignment i by superscripting the constant or expression with i as the superscript.

| p(a)i = 1 | q(a,a)i = 0 | q(b,a)i = 1 |

| p(b)i = 0 | q(a,b)i = 1 | q(b,b)i = 0 |

Given a truth assignment for ground atoms, the semantics of our language gives us a truth assignment for all sentences in the language - not just the ground atoms but also logical sentences and quantified sentences. For example, given the truth assignment shown above, we know that the complex sentence we saw earlier must be true.

∀x.(p(x) ⇒ ¬q(x,x))i = 1

A sentence is valid if and only if it is satisfied by every truth assignment. For example, the sentence (p(a) ∨ ¬p(a)) is valid. If a truth assignment makes p(a) true, then the first disjunct is true and the disjunction as a whole true. If a truth assignment makes p(a) false, then the second disjunct is true and the disjunction as a whole is true.

A sentence is unsatisfiable if and only if it is not satisfied by any truth assignment. For example, the sentence (p(a) ∧ ¬p(a)) is unsatisfiable. No matter what truth assignment we take, the sentence is always false.

A sentence is contingent if and only if there is some truth assignment that satisfies it and some truth assignment that falsifies it. For example, the sentence (p(a) ∧ q(a,a)) is contingent. If p(a) and q((a),(a)) are both true, it is true. If p(a) and q(a,(a)) are both false, it is false.

A sentence φ is logically equivalent to a sentence ψ if and only if every truth assignment that satisfies φ satisfies ψ and every truth assignment that satisfies ψ satisfies φ. The sentence ¬(p ∨ q) is logically equivalent to the sentence (¬p ∧ ¬q). If p and q are both true, then both sentences are false. If either p is true or q is true, then the disjunction in the first sentence is true and the sentence as a whole false. Similarly, if either p is true or q is true, then one of the conjuncts in the second sentence is false and so the sentence as a whole is false. Since both sentences are satisfied by the same truth assignments, they are logically equivalent.

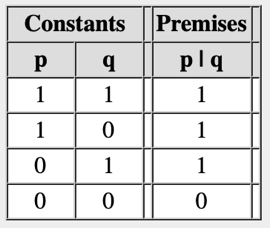

A sentence φ logically entails a sentence ψ (written φ ⊨ ψ) if and only if every truth assignment that satisfies φ also satisfies ψ. For example, the sentence p logically entails the sentence (p ∨ q). Since a disjunction is true whenever one of its disjuncts is true, then (p ∨ q) must be true whenever p is true. On the other hand, the sentence p does not logically entail (p ∧ q). A conjunction is true if and only if both of its conjuncts are true, and q may be false. Of course, any set of sentences containing both p and q does logically entail (p ∧ q).

A sentence φ is consistent with a sentence ψ if and only if there is a truth assignment that satisfies both φ and ψ. A sentence ψ is consistent with a set of sentences Δ if and only if there is a truth assignment that satisfies both Δ and ψ. For example, the sentence (p ∨ q) is consistent with the sentence (¬p ∨ ¬q). However, it is not consistent with (¬p ∧ ¬q).

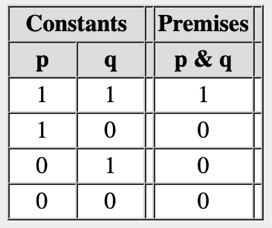

Equivalence, entailment, and consistency can be determined by comparing truth tables. We first determine which truth assignments satisfy the two sentences and then compare. If the the set of truth assignments that satisfy the sentences are the same, the sentences are equivalent. If the set of truth assignments that satisfies the first is a subset of the set of truth assignments that satisfy the second (as in the case below), then the first sentence logically entails the second. And, if there is at least one truth assignment that satisfies both, the sentences are consistent.

Unfortunately, truth tables and logic grids can be very large or even infinite, rendering this approach impractical or even impossible. Fortunately, there is another way of validating these properties and relationships.

A proof of a conclusion from a set of premises is a sequence of sentences terminating in the conclusion in which each item is either (1) a premise, (2) an instance of an axiom schema, or (3) the result of applying a rule of inference to earlier items in sequence.

| 1. | p | Premise |

| 2. | p ⇒ q | Premise |

| 3. | (p ⇒ q) ⇒ (q ⇒ r) | Premise |

| 4. | q | Implication Elimination: 2, 1 |

| 5. | q ⇒ r | Implication Elimination: 3, 2 |

| 6. | r | Implication Elimination: 5, 4 |

A proof system is sound if and only if every provable conclusion is logically entailed, i.e. if there is a proof of a sentence φ from a set of sentences Δ, then Δ logically entails φ.

If Δ ⊢ φ, then Δ ⊨ φ.

A proof system is complete if and only if every logical conclusion is provable ,i.e. if Δ logically entails φ, then there is a proof of a sentence φ from Δ.

If Δ ⊨ φ, then Δ ⊢ φ.

There is a proof procedure for Propositional Logic that is both sound and complete. Moreover, the question of logical entailment for Propositional Logic is decidable - there is an effective procedure that takes any premise and any conclusion as arguments and terminates in finite time with an indication of whether or not the premise logically entails the conclusion.

The same holds true for Relational Logic. There is a sound and complete proof procedure, and the question of logical entailment is decidable.

Herbrand Logic is more expressive than Propositional Logic and Relational Logic - it is possible to define things in Herbrand Logic that cannot be defined in either of the other two logics. Unfortunately, there is no sound and complete proof procedure for Herbrand Logic, and the question of logical entailment for Herbrand Logic is not decidable.

17.3 Extensions

Deduction is reasoning from premises to conclusions that are logically entailed by the premises. In other words, it is sound reasoning; if we are able to deduce a conclusion from a set of premises, it must be true whenever the premises are true.

All men are mortal.

Socrates is a man.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

|

It is noteworthy that there are patterns of reasoning that are sometimes useful but do not satisfy this strict criterion. There is inductive reasoning, abductive reasoning, reasoning by analogy, and so forth.

Induction is reasoning from the particular to the general. The example shown below illustrates this. If we see enough cases in which something is true and we never see a case in which it is false, we tend to conclude that it is always true.

I have seen 1000 black ravens.

I have never seen a raven that is not black.

Therefore, every raven is black.

Now try red Hondas.

|

Induction is the basis for Science. Deduction is the subject matter of Logic. Science aspires to discover new knowledge. Logic aspires to derive conclusions implied by things we know or assume to be true.

Abduction is reasoning from effects to possible causes. Many things can cause an observed result. We often tend to infer a cause even when our enumeration of possible causes is incomplete.

If there is no fuel, the car will not start.

If there is no spark, the car will not start.

There is spark.

The car will not start.

Therefore, there is no fuel.

What if the car is in a vacuum chamber?

|

Reasoning by analogy is reasoning in which we infer a conclusion based on similarity of two situations, as in the following example.

The flow in a pipe is proportional to its diameter.

Wires are like pipes.

Therefore, the current in a wire is proportional to diameter.

Now try price.

|

Of all types of reasoning, deduction is the only one that guarantees its conclusions in all cases, it produces only those conclusions that are logically entailed by one's premises.

|